Introduction

Rural health and access to care has been a concern to health care providers and policymakers for many years. The daunting combination of a scarcity of health care resources; enduring poverty; and challenges related to education, technology, transportation, and infrastructure have resulted in widespread and growing health disparities for people living in rural areas, relative to their urban neighbors. My colleagues at the AAMC Research and Action Institute have published a paper1 on these challenges. Efforts to ensure an adequate health workforce to address rural health needs have achieved mixed outcomes — recruitment has increased, yet rural health disparities remain. Most public policy focuses on recruiting providers to work in these underserved communities. In this paper, I present data from New York to illustrate the outcomes of these efforts and suggest potential avenues to enhance these outcomes and better address rural health disparities. While the data show New York’s efforts to be highly successful in recruiting providers into rural areas, the lesson learned is that additional measures are needed.

Spotlight on New York: Physician Production and Rural Workforce Recruitment Efforts

Physician Production

To provide some insight on the challenges rural areas have recruiting health care providers, a glimpse of data from one state, New York, is helpful. Why New York? In terms of the production of new physicians nationally, New York is the largest contributor.2 Currently, the state has more than 11,000 students enrolled in 17 medical and osteopathic programs3-5 and more than 19,000 residents and fellows in 1,400 accredited graduate medical education programs, figures that exceed those in the next closest state (California) by more than 36% and 21%, respectively.6 No other state trains more physicians than New York.

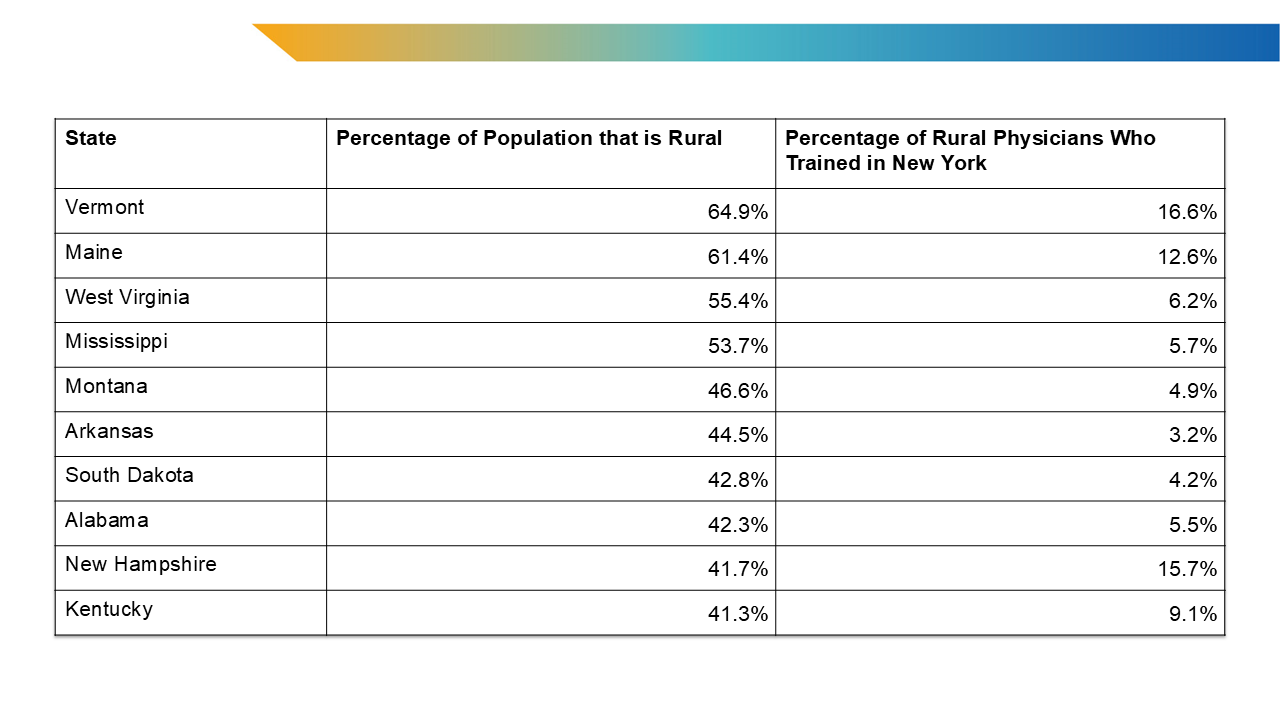

Slightly more than half of the physicians who complete training each year leave New York to practice elsewhere.2 Of all the physicians who were actively practicing in the United States in 2022, 17% completed a residency or fellowship in New York, and of those who were practicing in rural areas, 9% completed a residency or fellowship in New York.2 In examining states with the greatest percentages of their populations living in rural areas (Table 1), New York trains a substantial portion of these states’ physician workforces, especially the states closest to New York.

Table 1. Percentage of New York-Trained Physicians in the States With the Highest Rural Populations

Sources: Forte G. Graduate Medical Education in New York: The Nation’s Largest Supplier of Physicians. Center for Health Workforce Studies, School of Public Health, University at Albany - State University of New York; 2023. Accessed March 27, 2025. https://www.chwsny.org/GMENYbrief2023 U.S. Census Bureau. URBAN AND RURAL. Decennial Census, DEC 118th Congressional District Summary File, Table P2. Accessed April 9, 2025. https://data.census.gov/table/DECENNIALCD1182020.P2?q=rural%20population

The Center for Health Workforce Studies (CHWS) at the University at Albany - State University of New York (SUNY) conducts an annual survey of all physicians who complete training in New York. Since 2010, around 5% of survey respondents have gone into rural practice after training (Figure 1). Physicians completing training in primary care specialties; are non-U.S. citizen international medical graduates, especially those on exchange visitor (J-1) visas; and those who completed training in federally sponsored Teaching Health Center Graduate Medical Education (THCGME) programs have been most likely to enter practice in rural areas upon completion of their graduate medical education in New York.

Health Workforce Recruitment

Several state and federal programs exist to recruit providers to practice in rural areas by providing education, training, and rural practice exposure across the country, with varying levels of success in New York. A program offered at SUNY Upstate Medical University, the Rural Medical Education program (RMED), is an elective training experience for medical students that has seen historical success. An evaluation of the program found that RMED participants were about 3.5 times more likely to practice in rural areas than SUNY Upstate Medical University graduates who had not participated in the program (26% compared to 7%, respectively). In addition, more than 80% of participants were satisfied with their practice location choice and indicated that the RMED program was influential in their decision.7 Building on the documented success of the RMED program, in 2007, SUNY Upstate Medical University launched the Rural Medical Scholars Program. The objective of this program was to double the number of students participating in the RMED program by actively identifying, recruiting, and mentoring students from rural, small-town, and underserved communities, who were interested in returning to those communities to practice.8

Federally sponsored programs like THCGME, Teaching Health Center Planning and Development (THCPD), and Rural Residency Planning and Development (RRPD), are part of the Public Health Service Act Title VII program, and they support primary care education and training programs. These programs support the training of physicians and dentists and the establishment of medical and dental residency programs in rural and underserved areas,9 and provide start-up funding for rural residency programs.10 As of 2024, five THCGME programs exist in New York (three focus on family medicine, one on internal medicine, and another on psychiatry), and physicians who have completed these programs have entered rural practice at higher rates than most of those who completed other programs in the state. In addition, more than 27% of physicians who completed training at a THCGME program in New York reported their initial practice position in a rural area. Within New York in 2024, there were 18 residency programs offering rural rotations (two of which are RRPD program recipients) and eight THCPD awardees.11

Other education- and training-focused, federally sponsored programs include the National Health Service Corps (NHSC)12 and Nurse Corps,13 designed to help train new primary care and nursing providers to work in medically underserved areas. Programs focused on undergraduate and graduate medical education encourage rural physician practice by providing students and trainees with rural clinical experiences. These programs are premised on findings that education and training experiences in rural and other underserved settings increase the likelihood of physicians ultimately choosing to practice in rural locations.14-24

Posttraining support includes a variety of additional NHSC and Nurse Corps programs, such as loan repayment,25,26 students to service,27 and rural community loan repayment.28 Posttraining programs typically require a service obligation to practice in a designated underserved area for a defined amount of time in exchange for some benefit to the provider. Other federal service obligation programs target specific substantive areas, including pediatrics29 and substance use disorder prevention and treatment.30 While these programs are not specifically targeted for rural communities (except the NHSC Rural Community Loan Repayment Program), many rural communities meet the eligibility criteria for provider participation.

Another federal program, the Conrad 30 waiver program, allows each state to recommend up to 30 applicants to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services for a waiver of the two-year foreign residency requirement after completion of graduate medical education on a J-1 visa in exchange for service in a designated medically underserved area.31 New York takes full advantage of this program, having used 100% of its allotment of slots between 2001 and 2020.32 While these programs are not specifically targeted for rural communities, 21% of Conrad 30 placements in New York between 2004 and 2020 were in rural areas.32

In addition, to encourage health professionals to practice in health facilities serving American Indian and Alaska Native populations, the Indian Health Service offers a loan repayment program that requires a two-year service obligation.33 The vast majority of the eligible locations for this program are located in rural areas.34

Various New York entities also sponsor a host of health workforce recruitment programs. The programs support the recruitment of physicians, oral health professionals (e.g., dentists and dental hygienists), nurses (e.g., advanced practice nurses, registered nurses, and licensed practice nurses), behavioral health professionals (e.g., social workers, mental health counselors, marriage and family therapists, and psychologists), and others (e.g., respiratory therapists, radiologic, surgical, and clinical laboratory technologists). The programs generally take the form of either a scholarship or loan repayment in exchange for various lengths of service in underserved settings, areas, or populations.35 As of March 2022, about 350 providers were participating in these state-sponsored programs.36 One example is the Doctors Across New York series of programs, which offers loan repayment for physicians practicing in underserved areas. Doctors Across New York also offers support to eligible health care facilities and practices to help defray costs related to recruiting physicians, and to physicians to help defray costs related to establishing a practice in an underserved area.37

As of March 2022, there were more than 2,000 providers participating in federally and state- sponsored health workforce recruitment programs in New York.36 Rural areas significantly benefit from these programs, with more than a quarter of the programs’ participants meeting their service obligations in rural areas. Primary care and behavioral health providers in rural areas make up 14.5% and 9.6%, respectively, of all participants. In terms of individual professions, physicians and nurse practitioners make up the greatest number of participants in rural areas: 179 and 131 providers, respectively (Tables 2 and 3).

As a final note, in January 2024 the New York State Department of Health received approval for several amendments to its Section 1115 Waiver with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid. As part of the amendments, several workforce initiatives have been established to support both the recruitment and the retention within the health workforce that serves uninsured people and those insured through Medicaid; this includes a sizable portion of the rural population in the state. Along the same lines as other workforce strategies, these new initiatives involve targeted loan repayment to address acute, long-standing issues related to care access. In addition, the initiatives also provide social supports to help make becoming a health professional or advancing within a profession easier.38,39

Effects on Rural Health Disparities in New York

Despite the success of the efforts above to recruit health care providers into the state’s rural areas, New York’s rural population continues to experience health disparities, relative to urban residents. Much like the experience in other parts of the country,40-58 New York’s rural population experiences poorer health outcomes compared to the urban population, including lower life expectancy; greater years of potential life lost; more days being physically and mentally unhealthy; and higher rates of drug overdose mortality, suicide, and adult, child, and infant mortality. In addition, rural areas in New York also experience disparities in health care access, including higher proportions of uninsurance and fewer primary, oral health, and behavioral health care providers per capita, leading to higher rates of unmet needs.59-65

Where Do We Go From Here?

Current approaches to improving the health of rural communities have focused almost exclusively on recruiting primary care providers to practice in rural areas. Even with the success in increasing the likelihood that more health care providers will practice in rural areas, health and health care access disparities in these areas have continued to grow. Moreover, as spotlighted above, federally and state-sponsored efforts in New York have resulted in the recruitment of thousands of care team members, yet disparities in rural health and access to care remain.

With respect to the rural physician workforce, in particular, recruiting medical students and residents with rural backgrounds and origins is becoming increasing more difficult as the pool of candidates becomes smaller due to fewer rural students enrolling in medical school,66,67 as well as persistent education-attainment gaps between rural and nonrural populations.68 In addition, the focus on recruitment with limited expectation of retention in rural areas beyond a specified obligation period has not led to a robust, stable physician workforce meeting the demand for services, nor has it closed the gap between available urban and rural health care access, as documented by physician relocation behavior.69 These observations may be generalized to other health professions, as well.

While current policies and programs are necessary and of significant benefit to both the participating providers and the populations they serve, additional approaches need to be considered since the rural health care access gaps and the associated rural mortality rate are not being effectively reduced.70 Below, I offer suggestions for reinforcing existing successful efforts and for making changes to rural health workforce policy. These suggestions are meant as modest contributions to the ongoing discussion of how best to address rural health and workforce disparities.

Addressing Social Determinants of Health

First, improving rural health by effecting workforce policy will produce the desired outcomes only in concert with addressing social determinants of health. Even with an adequately sized and trained workforce, health in rural communities will suffer if the social determinants of health, including poverty, educational attainment, and access to technology and transportation, are not addressed. As social determinants of health may account for as much as 50% of variation in health outcomes, they cannot be ignored.71 Some, but not all, evidence suggests interventions that address social needs yield improvements in health outcomes, especially when multiple needs are addressed.71-73 Recent recommendations from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine provide a wide-ranging series of activities to transform health care delivery, the health workforce, technology, and health care finance that would help address social determinants by integrating social needs into health care delivery.74 These recommendations acknowledge the delivery of care through interprofessional teams to address social determinants of health. In a previous paper,75 I examined how understanding how care is provided by care teams is important for improving the effectiveness of health policy in addressing health workforce challenges.

Supporting and Expanding Current Workforce Recruitment Efforts and Policies

Programs like SUNY Upstate Medical University’s Rural Medical Scholars Program and Thomas Jefferson University’s Physician Shortage Area Program76 in Pennsylvania may be successful models to base future efforts on. Federal programs that help facilitate the efforts to identify, train, and mentor students for health careers in rural areas should continue. Further efforts to target portions of graduate medical education support (e.g., RRPD and THCPD) could also be continued and expanded to reinforce existing interest in rural practice among physicians. Without successful efforts like these, existing rural health disparities would grow more quickly; however, these efforts need to be supplemented.

The current supplements to these efforts are in the form of federal- and state-sponsored loan repayment and visa waivers in exchange for service provided in designated shortage areas. While these programs are successful with many participants, they focus on recruitment rather than retention, so miss an important opportunity to be more effective, especially in rural areas, which are chronically medically underserved. To improve these programs, several parameters could be revised: Following the example of New York, classify all rural areas as eligible regardless of their shortage designation status. While this would ensure that all rural areas are eligible for participant placement, it would not address the retention issue, so to improve retention in rural areas, remove service time restrictions to make participation in the programs open-ended. In the case of loan repayment, the effect of this kind of revision would be subsidized rural practice. This revision is also a nod to and extension of the Doctors Across New York Practice Support program, as it acknowledges that decisions to establish a practice (and remain in practice) are more complex than simply paying down an already incurred debt.

Beyond these efforts, however, policymakers need to better understand what investments can be made to improve access to services across health care, including specialty, surgical, maternal, and mental health care — especially improvements that can be achieved without relying on a monumental clinician relocation effort to rural areas.

Understanding the Dynamics of Rural Health Care Needs

Rural communities are not a monolith; when you have seen one community, you have seen only one.77-84 Solutions to disparities in health and access to care in rural areas require a much better understanding of the dynamics involved; further, there are the specific needs of rural communities, as well as the needs of specific rural communities. Much of the work identifying the challenges related to rural health and access to care presents findings from comparing rural and urban (or nonrural or metropolitan) areas and sometimes within rural-area classifications (e.g., rural-urban continuum codes). While it is, of course, important to develop generalized knowledge, especially to raise awareness in the policy community, it is also important to appreciate the diversity of factors (population demographics, economy, health care needs, barriers to care, workforce challenges, etc.) and the dynamics of them within rural areas. Developing successful policy requires more specific information about the target communities, and the policy itself needs to be flexible enough to fit the specific needs of a local area or region. Local needs assessments developed through collaborations between public and private stakeholders invested in the community can help shape the development of tailored training, recruitment, and retention strategies targeting health care providers, to improve access to care for a community;78,84,85 it is critical for success that these strategies are locally driven, flexible, and adaptable to variable environments with limited resources.78,84

The establishment of technical assistance centers that can work directly with local communities is warranted, to devise strategies for addressing community-specific challenges related to the health workforce and access to care. Examples of such efforts include the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy’s Rural Maternal Health Data Support and Analysis Program.86 The purpose of this program is to provide rural maternal health care networks with technical support and assistance around data collection and analysis to improve maternal health care locally. Another example is the National Center for Health Workforce Analysis’ Health Workforce Technical Assistance Center, which provides technical assistance to states and organizations that engage in health workforce planning and develop policy that addresses current health workforce challenges.87 This kind of technical assistance can help rural communities understand the range of strategies that have been employed successfully elsewhere, adapt them to meet local needs, and evaluate their impact.

Promoting Strategies That Improve Access to Care

Promoting existing strategies that improve access to care in rural areas is as important as developing new ones. In this vein, above I recommended continuing to use recruitment incentive programs as supplements to training new health care providers for rural practice. Another strategy that has documented success at improving access to care in rural areas is Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes).88-90 This model, originally developed to address the limited capacity for hepatitis C treatment in rural New Mexico, brings together rural health care providers and disease-specific consultants through telementoring (e.g., training, advising, and supporting local providers); as a result, the capacity of rural providers to manage complex medical conditions is increased. Using a different approach, the AAMC program, Project CORE® (Coordinating Optimal Referral Experiences), has also documented success at improving access to specialty care. In the Project CORE model, primary care providers connect with specialists asynchronously using eConsults;91 evidence to date suggests successful application in a number of specialties and rural areas.88,92 Continued funding and promotion of these models could help address the specialty treatment disparities experienced in many rural areas.

In addition to supporting existing efforts for providing health care services to people in rural areas, it is also important to promote strategies that have successfully facilitated access to care, including federally sponsored community health centers, insurance coverage through the Affordable Care Act and Medicaid, as well as telehealth.

Moving Away From Provider-to-Population Ratios: Identifying Better Metrics

Finally, policy discussions around the health care workforce often get stuck on the number of a specific kind of provider or a provider-to-population ratio. In fact, some of the eligibility criteria for federal designation of shortage areas encompass just those kinds of measures. Focusing on provider-to-population ratios may not be ideal to address the challenges related to health disparities and access to care in rural areas; focusing instead on population health and other health system performance metrics could be more useful. As I described in a previous paper,75 care is provided by some variation of an interprofessional team — even if it is a team of one. While rural areas have limited resources, and health provider resources are likely to be low regardless of policy decisions, there is tremendous variation in the ways in which care can be provided successfully. Acknowledging this variation, a better way to measure and compare different care configurations is by performance rather than a count of providers and/or the credentials they hold. While this change may increase the complexity of developing models to project future workforce adequacy (see my previous paper93), it is more desirable because it emphasizes the importance of the outcome (performance) over an input (supply). A good place to find potential performance metrics is Healthy People 2030,94 a robust set of national objectives and indicators of health and well-being. Using resources like Healthy People 2030 provides local communities with benchmark comparisons, as well as the ability to set location-specific performance goals.

Final Thoughts

Efforts to recruit providers into rural areas have been successful and remain a necessary intervention to address rural health disparities. As presented above, New York has successfully taken advantage of federally funded opportunities and has established its own successful interventions. There is room for improvement, of course. For example, the singular focus of these strategies should be supplemented with additional efforts to retain the recruited providers. In line with my AAMC colleagues' thoughts, however, it must be recognized that these necessary efforts are not sufficient, as evidenced by continued and worsening health disparities in rural areas.1 If the goal is to improve rural health, ensuring an adequate workforce is but one part of a broader effort.

References

- Orgera K, Senn S, Grover A. Rethinking Rural Health. AAMC; 2023. doi:10.15766/rai_xmxk6320

- Forte G. Graduate Medical Education in New York: The Nation’s Largest Supplier of Physicians. Published January 20, 2023. Accessed April 7, 2025. https://www.chwsny.org/our-work/reports-briefs/graduate-medical-education-in-new-york-the-nations-largest-supplier-of-physicians-2/

- Barzansky B, Etzel SI. MD-granting medical schools in the US, 2022-2023. JAMA. 2023;330(10):977-987. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.15521

- American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine. New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine - NYITCOM. Accessed April 7, 2025. https://www.aacom.org/detail-pages/com/new-york-institute-of-technology-college-of-osteopathic-medicine

- American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine. Touro College of Osteopathic Medicine - TouroCOM. Accessed April 7, 2025. https://www.aacom.org/detail-pages/com/touro-college-of-osteopathic-medicine

- Brotherton SE, Etzel SI. Graduate medical education, 2022-2023. JAMA. 2023;330(10):988-1011. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.15520

- Smucny J, Beatty P, Grant W, Dennison T, Wolff LT. An evaluation of the Rural Medical Education Program of the State University Of New York Upstate Medical University, 1990-2003. Acad Med. 2005;80(8):733-738. doi:10.1097/00001888-200508000-00006

- SUNY Upstate Medical University. Family medicine frequently asked questions. Accessed April 7, 2025. https://www.upstate.edu/fmed/education/rmed/faqs.php

- Health Resources and Services Administration. Teaching Health Center Planning and Development Program. Accessed April 7, 2025. https://www.hrsa.gov/grants/find-funding/HRSA-23-015

- Health Resources and Services Administration. Rural Residency Planning and Development (RRPD) Program. Updated February 2025. Accessed April 7, 2025. https://www.hrsa.gov/rural-health/grants/rural-health-research-policy/rrpd

- Health Resources and Services Administration. Rural Residency Planning and Development (RRPD) Program awards. August 2024. Accessed April 7, 2025. https://www.hrsa.gov/rural-health/grants/rural-health-research-policy/rrpd/awards

- Health Resources and Services Administration. NHSC Scholarship Program overview. March 2025. Accessed April 7, 2025. https://nhsc.hrsa.gov/scholarships/overview

- Health Resources and Services Administration. Nurse Corps Scholarship Program. Published online March 5, 2024. Accessed July 29, 2024. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bureau-health-workforce/funding/nursecorps-sp-guidance.pdf

- Castro MG, Roberts C, Hawes EM, Ashkin E, Page CP. Ten-year outcomes: community health center/academic medicine partnership for rural family medicine training. Fam Med. 2024;56(3):185-189. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2024.400615

- Patterson DG, Shipman SA, Pollack SW, et al. Growing a rural family physician workforce: the contributions of rural background and rural place of residency training. Health Serv Res. 2024;59(1):e14168. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14168

- Pollack SW, Andrilla CHA, Peterson L, et al. Rural versus urban family medicine residency scope of training and practice. Fam Med. 2023;55(3):162-170. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2023.807915

- Phillips RL Jr, George BC, Holmboe ES, Bazemore AW, Westfall JM, Bitton A. Measuring Graduate Medical Education Outcomes to Honor the Social Contract. Acad Med. 2022;97(5):643-648. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004592

- Russell DJ, Wilkinson E, Petterson S, Chen C, Bazemore A. Family medicine residencies: how rural training exposure in GME is associated with subsequent rural practice. J Grad Med Educ. 2022;14(4):441-450. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-21-01143.1

- Hawes EM, Fraher E, Crane S, et al. Rural residency training as a strategy to address rural health disparities: barriers to expansion and possible solutions. J Grad Med Educ. 2021;13(4):461-465. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-21-00274.1

- Schmitz D. The Role of Rural Graduate Medical Education in Improving Rural Health and Health Care. Fam Med. 2021;53(7):540-543. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2021.792533

- United States Government Accountability Office. Graduate Medical Education: Programs and Residents Increased During Transition to Single Accreditor; Distribution Largely Unchanged. Published April 2021. Accessed April 7, 2025. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-21-329.pdf

- Mullan F, Chen C, Steinmetz E. The geography of graduate medical education: imbalances signal need for new distribution policies. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(11):1914-1921. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0545

- Phillips RL, Petterson S, Bazemore A. Do Residents Who Train in Safety Net Settings Return for Practice? Acad Med. 2013;88(12):1934-1940. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000025

- Rabinowitz HK, Diamond JJ, Markham FW, Wortman JR. Medical school programs to increase the rural physician supply: a systematic review and projected impact of widespread replication. Acad Med. 2008;83(3):235-243. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e318163789b

- Health Resources and Services Administration. NHSC Loan Repayment Program. Updated March 2025. Accessed April 7, 2025. https://nhsc.hrsa.gov/loan-repayment/nhsc-loan-repayment-program

- Health Resources and Services Administration. Nurse Corps Loan Repayment Program: Fiscal Year 2025 Application and Program Guidance, 2025. Accessed April 7, 2025. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bureau-health-workforce/funding/nursecorps-lrp-guidance.pdf

- Health Resources and Services Administration. NHSC Students to Service Loan Repayment Program. Updated November 2024. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://nhsc.hrsa.gov/loan-repayment/nhsc-students-to-service-loan-repayment-program

- Health Resources and Services Administration. NHSC Rural Community Loan Repayment Program. Updated March 2025. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://nhsc.hrsa.gov/loan-repayment/nhsc-rural-community-loan-repayment-program

- Health Resources and Services Administration. Apply to the Pediatric Specialty Loan Repayment Program. July 2024. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/funding/apply-loan-repayment/pediatric-specialty-lrp

- Health Resources and Services Administration. NHSC Substance Use Disorder Workforce Loan Repayment Program. March 2025. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://nhsc.hrsa.gov/loan-repayment/nhsc-sud-workforce-loan-repayment-program

- United States Citizenship and Immigration Services. Conrad 30 Waiver Program. January 25, 2025. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://www.uscis.gov/working-in-the-united-states/students-and-exchange-visitors/conrad-30-waiver-program

- Ramesh T, Brotherton SE, Wozniak GD, Yu H. An increasing number of states filled Conrad 30 waivers for recruiting international medical graduates. Health Aff Sch. 2024;2(9):qxae103. doi:10.1093/haschl/qxae103

- Indian Health Service. Loan Repayment Program. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://www.ihs.gov/loanrepayment/

- Indian Health Service. IHS, Tribal, & Urban Indian Health Facilities List - Released June, 2023. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://www.ihs.gov/sites/locations/themes/responsive2017/display_objects/documents/ihs_facilities.xlsx

- CHWS. The Hub for Health Workforce Shortages: service-obligated programs. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://shortagehub.com/#/serviceobligatedprograms

- Martiniano R, Romero A, Moore J. Service-Obligated Providers in New York State. Published May 2023. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://www.chwsny.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/CHWS_NY-Service-Obligated-Programs-Brief_2023.pdf

- New York State Dept. of Health, Division of Workforce Transformation. Solicitation of Interest #20472 - Doctors Across New York Physician Loan Repayment and Physician Practice Support Programs- Cycle X. Published March 14, 2024. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://www.health.ny.gov/professionals/doctors/graduate_medical_education/doctors_across_ny/docs/soi_cycle_x.pdf

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Project Number 11-W-00114/2 Special Terms and Conditions. Published January 9, 2024. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://www.health.ny.gov/health_care/managed_care/appextension/docs/2024-01-09_cms_ltr.pdf

- New York State Dept. of Health, New York Medicaid Redesign Team. 1115 Medicaid Redesign Team Waiver Webinar: New York Health Equity Reform (NYHER): 1115 Amendment Overview. Presented February 2024. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://www.health.ny.gov/health_care/medicaid/redesign/med_waiver_1115/docs/2024-02-16_nyher_overview_slides

- Singh GK, Daus GP, Allender M, et al. Social determinants of health in the United States: addressing major health inequality trends for the nation, 1935-2016. Int J MCH AIDS. 2017;6(2):139-164. doi:10.21106/ijma.236

- National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2017. Table 039: Number of respondent-reported chronic conditions from 10 selected conditions among adults aged 18 and over, by selected characteristics: United States, selected years 2002-2016. Hyattsville, MD. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/data-finder.htm

- Cohen SA, Greaney ML, Sabik NJ. Assessment of dietary patterns, physical activity and obesity from a national survey: rural-urban health disparities in older adults. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0208268. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0208268

- Shaw KM, Theis KA, Self-Brown S, Roblin DW, Barker L. Chronic disease disparities by county economic status and metropolitan classification, behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 2013. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:E119. doi:10.5888/pcd13.160088

- Morales DA, Barksdale CL, Beckel-Mitchener AC. A call to action to address rural mental health disparities. J Clin Transl Sci. 2020;4(5):463-467. doi:10.1017/cts.2020.42

- Rural Health Information Hub. Need for Substance Use Disorder Programs in Rural Communities - RHIhub Substance Use Disorders Toolkit. November 23, 2020. Accessed April 10, 2024. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/toolkits/substance-abuse/1/need

- Davis CN, O’Neill SE. Treatment of alcohol use problems among rural populations: a review of barriers and considerations for increasing access to quality care. Curr Addict Rep. 2022;9(4):432-444. doi:10.1007/s40429-022-00454-3

- CDC. Leading causes of death in rural America. Published August 27, 2024. Accessed April 15, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/rural-health/php/about/leading-causes-of-death

- Curtin SC, Spencer MR. Trends in death rates in urban and rural areas: United States, 1999-2019. NCHS Data Brief. 2021;(417):1-8. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/109049

- Garcia MC, Rossen LM, Matthews K, et al. Preventable premature deaths from the five leading causes of death in nonmetropolitan and metropolitan counties, United States, 2010-2022. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2024;73(2):1-11. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss7302a1

- Hedegaard H, Curtin SC, Warner M. Suicide Mortality in the United States, 1999-2017. National Center for Health Statistics. NCHS Data Brief. 2018;(330):1-8. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db330-h.pdf

- Pettrone K, Curtin SC. Urban-rural differences in suicide rates, by sex and three leading methods: United States, 2000-2018. NCHS Data Brief. 2020;(373):1-8. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db373-H.pdf

- Spencer MR, Garnett MF, Miniño AM. Urban-rural differences in drug overdose death rates, 2020. NCHS Data Brief. 2022;(440):1-8. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db440.pdf

- Ullrich F, Mueller K. COVID-19 cases and deaths, metropolitan and nonmetropolitan counties over time (update). Rural Data Brief. 2023;(2020-9):1-8. https://rupri.public-health.uiowa.edu/publications/policybriefs/2020/COVID%20Longitudinal%20Data.pdf

- Weber L. Covid is killing rural Americans at twice the rate of people in urban areas. Kaiser Health News. Published September 30, 2021. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/covid-killing-rural-americans-twice-rate-people-urban-areas-n1280369

- Cross SH, Califf RM, Warraich HJ. Rural-urban disparity in mortality in the us from 1999 to 2019. JAMA. 2021;325(22):2312-2314. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.5334

- Abrams LR, Myrskylä M, Mehta NK. The growing rural-urban divide in US life expectancy: contribution of cardiovascular disease and other major causes of death. Int J Epidemiol. 2022;50(6):1970-1978. doi:10.1093/ije/dyab158

- Kirby JB, Yabroff KR. Rural-urban differences in access to primary care: beyond the usual source of care provider. Am J Prev Med. 2020;58(1):89-96. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2019.08.026

- Johnston KJ, Wen H, Joynt Maddox KE. Lack of access to specialists associated with mortality and preventable hospitalizations of rural Medicare beneficiaries. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(12):1993-2002. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00838

- University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. County health rankings & roadmaps. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/

- Health Foundation for Western & Central New York (HFWCNY). Community Health Needs and Opportunities in Rural Central New York. HFWCNY; 2024. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://hfwcny.org/wp-content/uploads/CNY-Rural-Health-report-digital-1.pdf

- HFWCNY. Community Health Needs and Opportunities in Western New York’s Southern Tier. HFWCNY; 2022. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://hfwcny.org/wp-content/uploads/Community-Health-Needs-and-Opportunitys-in-WNYs-Southern-Tier-Web-Version.pdf

- CHWS. New York State Health Workforce Data Guide. Accessed April 8, 2025. http://nyhealthdataguide.org

- Office of the New York State Comptroller, Office of Budget and Policy Analysis. Rural New York: Challenges and Opportunities. Office of the New York State Comptroller; 2023. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://www.osc.ny.gov/files/reports/pdf/challenges-faced-by-rural-new-york.pdf

- Harun N, Kang B, Fernando T, Surdu S. Oral Health Needs Assessment for New York State, 2024. CHWS; 2024. Accessed December 5, 2024. https://www.chwsny.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/CHWS-Oral-Health-Needs-Assessment-NYS-2024-Final.pdf

- Harris B, Gallant K, Mariani A. Mental Health in Rural New York: Findings and Implications of a Listening Tour With Residents and Professionals. University of Chicago; 2023. Accessed December 5, 2024. https://www.sbirteducation.com/_files/ugd/e278f7_45417d63154f40139965b09ff6e7a7cf.pdf

- Shipman SA, Wendling A, Jones KC, Kovar-Gough I, Orlowski JM, Phillips J. The decline in rural medical students: a growing gap in geographic diversity threatens the rural physician workforce. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(12):2011-2018. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00924

- Wendling AL, Shipman SA, Jones K, Kovar-Gough I, Phillips J. Defining Rural: The predictive value of medical school applicants’ rural characteristics on intent to practice in a rural community. Acad Med. 2019;94(11S Association of American Medical Colleges Learn Serve Lead: Proceedings of the 58th Annual Research in Medical Education Sessions):S14-S20. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002924

- National Center for Education Statistics. Educational attainment in rural areas. In: Condition of Education. U.S. Dept. of Education, Institute of Education Sciences; 2023. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/lbc/educational-attainment-rural

- Hu X, Dill MJ, Conrad SS. What moves physicians to work in rural areas? An in-depth examination of physician practice location decisions. Econ Dev Q. 2022;36(3):245-260. doi:10.1177/08912424211046600

- Cosby AG, McDoom-Echebiri MM, James W, Khandekar H, Brown W, Hanna HL. Growth and Persistence of Place-Based Mortality in the United States: The Rural Mortality Penalty. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(1):155-162. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2018.304787

- Whitman A, De Lew N, Chappel A, Aysola V, Zuckerman R, Sommers BD. Addressing Social Determinants of Health: Examples of Successful Evidence-Based Strategies and Current Federal Efforts. Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation Office of Health Policy; 2022. Accessed April 8, 2025. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/e2b650cd64cf84aae8ff0fae7474af82/SDOH-Evidence-Review.pdf

- Yan AF, Chen Z, Wang Y, et al. Effectiveness of social needs screening and interventions in clinical settings on utilization, cost, and clinical outcomes: a systematic review. Health Equity. 2022;6(1):454-475. doi:10.1089/heq.2022.0010

- Tyris J, Keller S, Parikh K. Social risk interventions and health care utilization for pediatric asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176(2):e215103. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.5103

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Care Services; Committee on Integrating Social Needs Care into the Delivery of Health Care to Improve the Nation's Health. Integrating Social Care Into the Delivery of Health Care: Moving Upstream to Improve the Nation’s Health. National Academies Press (US); 2019. Accessed April 9, 2025. doi:10.17226/25467

- Forte G. How Improved Health Workforce Projection Models Could Support Policy. AAMC; 2024. doi:10.15766/rai_pfdisfs9

- Rabinowitz HK, Motley RJ, Markham FW Jr, Love GA. Lessons learned as Thomas Jefferson University’s rural Physician Shortage Area Program (PSAP) approaches the half-century mark. Acad Med. 2022;97(9):1264-1267. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004710

- Rural Health Information Hub. Rural healthcare workforce. Updated April 7, 2025. Accessed April 9, 2025. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/health-care-workforce#workforce

- Council on Graduate Medical Education. Strengthening the Rural Health Workforce to Improve Health Outcomes in Rural Communities. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Health Resources Administration; 2022. https://web.archive.org/web/20241120220000/https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hrsa/advisory-committees/graduate-medical-edu/reports/cogme-april-2022-report.pdf

- Lichter DT. Immigration and the new racial diversity in rural America. Rural Sociol. 2012;77(1):3-35. doi:10.1111/j.1549-0831.2012.00070.x

- Rural Health Information Hub. What is rural? Updated March 7, 2025. Accessed April 9, 2025. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/what-is-rural

- Rural Health Information Hub. Rural health disparities. March 24, 2025. Accessed April 9, 2025. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/rural-health-disparities

- Rural Health Information Hub. Education and training of the rural healthcare workforce. Updated March 19, 2025. Accessed April 9, 2025. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/workforce-education-and-training

- Rural Health Information Hub. Health and healthcare in frontier areas. 2023. Accessed June 4, 2024. https://web.archive.org/web/20250117212937/https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/frontier

- Temple KM. Frontline presence, building trust, emergency preparedness, and lessons learned: Q&A with Dr. Tim Putnam. Rural Monitor. January 10, 2024. Accessed April 9, 2025. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/rural-monitor/tim-putnam

- MacKinney AC, Coburn AF, Lundblad JP, McBride TD, Mueller KJ, Watson SD. Access to Rural Health Care – A Literature Review and New Synthesis. Rural Policy Research Institute; 2014. Accessed April 9, 2025. https://rupri.org/wp-content/uploads/20140810-Access-to-Rural-Health-Care-A-Literature-Review-and-New-Synthesis.-RUPRI-Health-Panel.-August-2014-1.pdf

- Health Resources and Services Administration. Rural Maternal Health Data Support and Analysis Program. Accessed April 9, 2025. https://www.hrsa.gov/grants/find-funding/HRSA-24-112

- Health Workforce Technical Assistance Center. About. Accessed April 9, 2025. https://www.healthworkforceta.org/about/

- Arora S, Thornton K, Murata G, et al. Outcomes of treatment for hepatitis C virus infection by primary care providers. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(23):2199-2207. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1009370

- Rural Health Information Hub. Project ECHO - Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes. Updated February 7, 2024. Accessed April 9, 2025. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/project-examples/733

- University of New Mexico. Project ECHO. Accessed April 9, 2025. https://projectecho.unm.edu/

- AAMC. About the CORE Program. Accessed April 9, 2025. https://www.aamc.org/about-us/mission-areas/health-care/project-core/about-core-program

- Avery J, Dwan D, Sowden G, Duncan M. Primary care psychiatry eConsults at a rural academic medical center: descriptive analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(9):e24650. doi:10.2196/24650

- Forte G. Why Health Workforce Projections Are Worth Doing. AAMC; 2023. doi:10.15766/rai_5xorzcnu

- U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Health People 2030 Framework. Accessed April 9, 2025. https://health.gov/healthypeople/about/healthy-people-2030-framework